On May 16th, 1946, we sailed from Garth Ferry in a flat calm with pouring rain and hail. Without a breath of wind there was no mistaking our departure, for the engine exhaust reverberated from side to side of the straits, and all our relatives and friends (even the old lady who had officially complained about our noise) turned out to wave us on our way.

She was designed for single-handed sailing, everything leads aft to the cockpit, and the only reasons to visit the fo'c'sle are to change or hoist the jib, or to chuck the anchor over the side. She is of sturdy chunky build, with the coach roof extending to either side. This gives the remarkable headroom of nearly 6ft and very good accommodation for her size. My husband and I are both of us very in long in the leg, and we lived aboard continuously for more than two months quite happily, plus a lot of personal gear and extra stores. Unfortunately there is no space on deck to stow our 8ft dingy, and for the whole of the 500 miles we had to tow it. It was certainly worth having a seaworthy tender in spite of it’s over affectionate habit of running up and bumping into Robinetta's transom both at sea and in harbour. At anchor a bucket over the stern was usually effective.

Robinetta spent her war years at Beaumaris on chocks in the open, and having fitted her out we were now sailing her round to Weymouth. One worthwhile thing we did was to take ample local advice for the awkward corners. The coxswain of the Beaumaris lifeboat was a friend of ours, and he recommended us to consult his opposite number in Fishguard and so on. We also had friends amongst the coast guards, and they were most helpful with advice and weather reports. They watched over us the whole way round with fatherly care – a few hours after we sailed from Dartmouth on our last hop they telephoned through to our home in Weymouth to say what time we should be wanting hot baths the following day!

The Swellies we knew, so they were soon negotiated and we clanked busily under the tubular bridge. To anyone who does not know this horrid patch well we would say it is essential to have minute directions from a local expert, and to learn them by heart or to follow another ship. The passage must be made at the top of slack high water, and the whole thing is so much smaller and narrower than one imagines from reading sailing directions that you must know what is coming by heart as there is no time to refer to books.

Caernarvon Bay was, to us, much worse. By this time a fresh breeze had sprung up against the tide and there was a short heavy sea. We had been told never to attempt it in these conditions, but we were in it before we know. With the short steep-to seas we made no progress plugging into the wind, so making full sail we kept the engine running and managed to beat slowly and bumpily out.

At 13.05 we dropped anchor in Pilot's Cove, Llandwyn Island, in four fathoms. In this cove there is comparative shelter from all winds with any west in them, and the bottom is hard sand. Apart from the single row of old coastguard cottages and the little lighthouse, there are no buildings on the island; no camping is allowed, so it is quite unspoilt. Mrs Jones (herself an ex-Caernarvon pilot) and her son, the lighthouse keeper are the only inhabitants, and Mrs Jones will give expert, if valuable, advice on the best spot to lie.

Next day looked perfect sailing weather, the BBC was optimistic and the coastguard reported favourable conditions all the way down. We set off at 11.00 on the 80 mile hop to Fishguard with a light NNE wind and high hopes. At first the wind was much lighter than we wanted, but by the end of the first 4 hours it was a perfect sailing breeze and we were spanking along at all of 4 knots, which is good for Robinetta towing a dingy. As we approached Bardsey Island the sky astern took on an evil purple colour and looked thoroughly menacing. We fixed our eyes ahead and sailed as fast as we knew - there was nothing else for it. We had been warned off trying to find shelter anywhere down the Welsh coast (off our route anyway) so we stuck to our course which, we hoped, would give us a landfall on Fishguard breakwater.

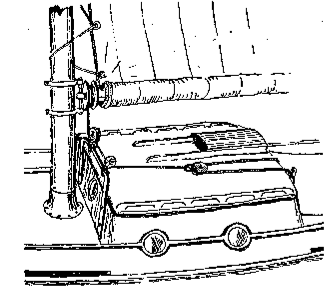

By 19.39 it was really blowing up, so we took three reefs in the mainsail and stowed the staysail. The only remarkable thing about Robinetta's roller reefing is that it has always worked and can be operated single handed from the cockpit. An iron horse is fixed to the forward end of the coachroofing, to which are shackled all the blocks for the halyards and reefing gear, which are then led aft to the cockpit. On the boom is a drum, around which is led ½ inch wire which follows through an iron block on the horse immediately below, through a second block on the port end of the horse, then aft to a wooden block midway to the cockpit. Through this block is a single purchase to the cockpit. The operation of reefing is carried out from the cockpit by slackening the peak and throat with one hand and heaving in on the reefing gear with the other hand – and round goes the boom as required.

All this reefing seemed over cautious, but we did not know our ship too well or what the unpleasant sky had in shore for us. An hour later it was beginning to be a bit tough, with a heavy beam sea and blowing strong from the NE, so in gathering gloom G. went forward to shift jibs.

The entries in our log from now on become a bit scrappy and difficult to read, but at 22.00 we wrote: “Full NE gale, Co. SSW/ Roaring along and luffing over the bigger seas. Raining intermittently and very cold. Just enough moonlight to see breaking seas in time to luff.” It was not really a full gale, but seemed even worse, luckily on the quarter – an exhilarating if anxious night.

We took hourly shifts at the helm to start with, but later, by mutual agreement G. did the lion's share for he did not care for struggling into the cabin and wedging himself in to consult the chart. The arrangement suited me, as I had somehow strained my shoulder, so beside navigating my job was to sit firmly in the forward weather corner of the cockpit and keep out any breaking seas with my broad back.

At 02.15. when the night seemed endless, the faint yellow flash of Strumble Head came winking through the wet darkness, bearing SW on the starboard bow exactly where we wanted it. A most cheering sight, and both of us felt better for seeing it. We crashed on, very cold, very wet, for another hour and a quarter, and sure enough dead ahead came the flashing red light on Fishguard breakwater. Morale became much higher. Especially as the wind had moderated slightly, though a heavy sea was still running.

At 05.30 we rounded Fishguard breakwater and looked round that dismal grey harbour for a snug berth. Thankfully we drank large mugs of comforting hot coffee and turned in – but not for long. By 08.00 we were both wide awake, with Robinetta dragging and plunging and snubbing at her cable to such an extent that we knew we should have to shift – but to where? The wind had risen again and was blowing straight through the harbour entrance and at us. The only thing for it was to ask advice. There was no sign of life anywhere, so with a certain amount of difficulty G. pulled ashore to the lifeboat house. An hour later he returned with Ben, the lifeboat coxswain, and we heaved up the anchor and steamed out of the harbour and across the bay to Lower Town.

We were weather-bound four days in Lower Town while the gale blew itself out. During that time we took the chance of going to St David's Head by bus just to see what the ill-famed Ramsey Sound did really look like and the lifeboat coxswain there pointed out the best passage through. When we made the passage once again we stuck rigidly to out local advice and were grateful for it. We got safely through, but in parts it was decidedly frightening.

On the afternoon of May 23 we sailed from Lower Town for Milford Haven. The day was bright, with light variable winds, while eventually died altogether, so almost the entire passage was deafening engine work. All was literally plain sailing for the first four hours until we turned the corner of St David's head into Ramsey Sound, with the tide under us and a faint breeze dead ahead. We motored straight down without mishap, passing some very ugly tide rips at the southern end. Course was then set to passage one mile west of Skomer Island – we had decided not to attempt Jack Sound. By this time there was no wind at all, but a big westerly swell, legacy from the recent gale, came rolling in. We gave us any attempt at sailing and stowed sail to stop the banging and slatting. At 18.30 we altered course round Skomer into Broad Sound and made for St Anne's Head. The glassy calm here made the madly swirling tide rips of each side look most uncanny, and we understood why people write about boiling eddies. We tried sailing once more to give ourselves a little peace and quiet, but it was no good, and we resigned ourselves to the racket for the rest of the passage. At last, with shattered ear drums and jagged nerves, we entered the Haven and dropped anchor in Dale Roads. It was 21.15 on a breathless, golden summer evening.

The world looked so lovely,and so peaceful that we are once decided to stay two days and to explore the estuary – thereby unconsciously missing the only good chance of getting across the Bristol Channel for a fortnight.

The morning of Saturday June 8, was beautifully calm with a good forecast. The many Londoners who set out in summer clothes with no umbrellas to watch the Victory procession will remember how wrong the forecast was, and Robinetta's crew will never forget. Mr Hanson's description of the Bristol Channel in the C.A. Handbook makes depressing reading, but every word is true! However at 06.15 it looked like being a wonderful passage, so we planned to catch the tide round Land's End and carry on to Penzance – if we made 3 or 3½ knots and had a fair wind it would be a 36 hour hop. We were under way at 06.15 and once clear of the Haven set course to pass 10 miles west of Lundy Island to get a fix, thence to a position off Trevose Head and parallel to the coast to Land's End.

For the first 20 miles until we sighted the grey shape of Lundy there was little wind and we had to disrupt the peace of the day with the engine to keep to our timetable. At 09.35 Lundy bore S25E, and course was altered to the position off Trevose Head 20 miles distant. There was a perfect light NWW breeze, so we set full sail, and by 13.30 Lundy was abeam and Hartland Point in sight. It was a pleasant afternoon, we held out course and were making a nice speed of 4 knots. Tintagel Head came up in the distance at 16.15 – so far all according to plan. Two hours later, almost simultaneously with a depressing forecast, our world began to look rather less pleasant. Our NW breeze had become a fresh westerly wind, so remembering out timely action in Cardigan Bay, we set the small jib and carried on. The time was 18.30, the log read 38 miles and Trevose Light was in sight.

Trevose Head and its light are things we neither of us ever want to see again – once we picked up the light we could not leave it, and it stayed with us all night.

By 20.30 there was quite a considerable westerly swell with a cross sea, the wind was still backing and freshening, till it was SW and heading us badly. We began looking for Godrevy light to come up, as according to our corrected-to-date chart and Reed's this light was visible for 17 miles. (When we got to St Ives we were reliably told that its strength had been reduced to show for 11 miles – as far as we know we never say the darn thing at all!) Two of three times we thought we had got it, and it disappeared to pop up again in a different place. Soon we realised that the rejoicing population of North Devon were celebrating the peace and confusing unwary mariners with bonfires and fireworks.

By the time darkness came we had changed our destination to St Ives, we were making so little progress against the buffeting sea – Robinetta will not point up under these conditions – and being headed so badly it was rather wearying work. We did not know the north Devon-Cornish coast and disliked the sound of Padstow even more than St Ives.

The remaining dark hours were a nightmare. With a dead beat to windward, a really heavy Atlantic swell and cross sea, poor Robinetta buffeted and smacked and staggered making, at times, about ½ a knot and at other times nothing at all. Dimly ahead the coast was flashing with lights, none of which we could identify at all. The hand bearing compass went mad, and try as we might we could get no sense out of it – one time we fixed ourselves on Dartmoor!

There was a fair amount of traffic about which ignored us dangerously, we thought, in spite of our wildly flashing torch, and these was little avoiding action we could take. Finding we were getting no closer to the land we tried a leg to sea. This brought us back to about the same place we had started from. We prayed for dawn when at least we might see where we were and whether we could turn and run for Padstow without broaching to – but Padstow had a doom bar... G clung desperately to the tiller, his face drawn and haggard. I, who like to think I was tough (and have since changed my mind), was having trouble with the strained shoulder, and am very ashamed to admit passed out for an hour on the cockpit floor.

Valiantly G. tried to hold the plunging little ship to her course, but her nose was being pushed more and more to the east with each wave. At 04.30, feeling something must be done about it, we stowed sails (no easy task in the violent motion) hauled in the log to reduce all possible hindrances, started the engine, and tried plugging into it. We refrained with difficulty from cutting the dingy adrift. Estimated speed was then about one knot. Half an hour later in the grey dawn we identified the square lump of St Agnes Head about five miles ahead and we stood inshore in the vain hope that there might be less sea running. An hour later St Agnes head was still as far off, the wind backing and freshening from SSW.

Came the dawn, red and flaming, which we both pretended not to see. Gradually, laboriously we closed St Agnes Head and then could not get past it. Heavy seas were washing over us; with difficulty we set shortened sail again and, still with the engine, beat uncomfortably and slowly towards the Stones off Godrevy Point.

We now appeared to be in St Ives Bay, with the wind straight off the land, and we thought that in such an off-shore wind we should be sheltered, but apparently not in the Bristol Channel. For two hours we flogged across the bay to St Ives, giving the Stones a side berth, and not until we were almost into the tiny harbour did we find calm water. The relief was amazing. One minute we were bouncing and plugging into it, and the next quite still. Down went the hook at once. We knew vaguely that we should dry out in two hours time and that we were right in the fairway, but so done in were we that down came sails, anchor and everything. The boom landed in an unseamanlike and painful fashion squarely on my head, but my seaman like comments were smothered in sail as I collapsed in the bottom of the cockpit.

As is well known, St Ives offers no shelter to the small visitor. The size of the mooring chains used by the fishermen is enough proof of what the run can be – they would hold a destroyer. So we embarked a pilot who had come alongside the moment we fetched up. He took one look at us (and a more bedraggled exhausted pair could scarcely be imagined) sent us below for hot food, shut the hatch, saying he would take us to Hayle. He heaved up the anchor himself and once more we were plugging into it, taking it green, but now with a lovely feeling of security. Half an hour later we were tied up alongside the highest wall I have ever seen in unbelievable stillness. There was no visible means of scaling this immense wall, the river was fast reducing itself to a muddy trickle, the surroundings – a deserted shipyard – were grim and the Cornish Riviera express roared over a bridge just ahead of us. Torrential rain poured down. But below, in the luxury of a still and so far dry cabin we cared nothing for the world about us and slept....

Once again we were weatherbound for several days while the strong Sou'-wester blew itself out, and then the tides forced us to spend one sleepless night in St Ives harbour before setting out on the hop round the corner to Newlyn.

At 05.40 on June 13 we cleared St Ives harbour under power to catch the tide round Land's End. Outside we found the inevitable westerly swell and a light WNW breeze. After passing St Ives Head we set course WSW to pass Pendeen lighthouse. Off this point we found heavy tide rips, so we stood out a little to avoid the breaking seas, and at 08.00 altered course to S by W to clear Longships. There was still very little wind and we were forced to keep the engine running, heavy confused seas with the westerly swell predominating made it uncomfortable going.

At 09.00 with Longships abeam to port about a mile off, the breeze died completely, leaving of course the swell and the much cursed but hitherto faithful engine coughed and died with the wind. The engineer was worried. He whipped off the engine cover, fiddled, cranked, blew through pipes and swore there was something very wrong beyond his capabilities. Three times she started and stopped within half an hour. All the time the tide was pushing us slowly but surely towards the ugly-looking rocks round the lighthouse, but the thing got itself going again for no very good reason and our troubles were over once more.

A few moments later we altered course for the Runnelstone buoy and felt that now we were really in the longed for Channel all would be well. And it is quite extraordinary how well everything became. The swell, of course, was now with us, but there was less of it, the reluctant sun came out and shone brightly and a pleasant westerly breeze came to. So off went the engine and we sailed peacefully and happily up to Newlyn, catching mackerel as we went.

By comparison, our voyage from Newlyn to Weymouth was uneventful. The South coast is so much better known, with more frequent harbours, that I will not tell out story in great detail. We sat back and enjoyed ourselves with pleasant day sails – only occasionally using the engine for its real purpose – coming into strange anchorages with foul tide or no wind.

From Newlyn we sailed to Helford, planning to spend two days in this lovely river. We did, but it never once stopped raining and our drip became a real leak. From Helford we sailed to St Mawes, where we got really hungry, and for the first time we found shopping a real problem.

On midsummer's day we left St Mawes for Fowey. The log records that it felt like the first day of real summer weather and not the end of flaming June, That night we anchored off Polruan, and spent a really hot week-end enjoying our surroundings and the famous hospitality of the Royal Fowey Yacht Club.

On June 24 reluctantly we left Fowey, and with the reaching jib set had a grand sail up to the Mew Stones at the entrance to the Yealm river. The entrance here is tricky, but the leading marks are good. And once up the river in the main yacht anchorage there is complete shelter from everything. Here once again the weather broke, fog and gales alternating, and we were tied up to a buoy for ten days.

Lovely as the Yealm is, we had not planned to stay there all of ten days. It was either gales or fog. Twice we ventured out to the mouth of the river, to be enveloped in thick fog which cut down out visibility to less than our own length. By now time, who had been so kind to us, was getting a bit short, so we decided to cut out our intended visit to Salcombe and make straight for Dartmouth, which was to be out jumping-off place for the trip across West Bay.

On Saturday, July 6, the BBC was really optimistic in their 08.00 forecast, so we chugged straight out of the Yealm and setting mainsail and reaching jib at the Mewstone, stopped the engine and set course for Bolt Tail. It was a cloudy day with a nice NE wind, and we had a good sail, averaging just over 4 knots, past Bolt Head, Prawle Point and up to N.Skerries buoy, which we reached by 16.00. Here the wind gradually died away, and for two hours we made very little progress save drift slowly sideways on to the Skerries Bank. So the engine once more was started and it pushed us into the Dart, where we made fast to a buoy off Kingswear and supped off our catch of mackerel.

Dartmouth was one of the most depressing sights of our voyage. It was, and I suppose still is, a graveyard of little ships who had fought the battle of the Narrow Seas. It was chock full of coastal craft of every type, from the little H.D.M.L to the newest M.T.B., some quite young destroyers and corvettes, and even a cruiser. We had both had a lot to do with the operation of little ships during the war, and the sight of these trots full of shabby, deserted, and unwanted shapes after all they had been through presented a melancholy picture indeed. So next morning, which promised to be a really hot one, we sailed up to Dittisham and basked in the sun.

Since April G. had been waiting for his anti-cyclone. He was sure that stationary anti-cyclones happen in the summer and then everything is all right. At long last this phenomenon had arrived and he was happy. This, however, did not prevent elaborate planning and preparation for the night passage round Portland Bill to out home port. Both our previous nights at sea were too fresh in our memories – in each case we had started out in good conditions, with good forecasts. This time the anti-cyclone won, and it was almost a flat calm for all the 63 miles we logged from Dartmouth to Portland Harbour.

There is very little of note about this leg of our journey. We sailed from Dartmouth at 18.00 on Monday, July 8, and picked up our own moorings in Castle Cove at 12.30 the following day. Breezes were light and fluctuating, and from every direction. Most of the time there was none at all, and for a great part of the night we were forced to shatter the strangely peaceful waters of West Bay with the engine. The trip is remembered by us chiefly because we were able to cook and eat large meals in complete comfort, and also to sleep. We gave Portland Bill a wide berth, which proved unnecessary, as this was one of the rare occasions when there was no race at all. As we approached the Shambles a pleasant westerly breeze sprang up, so we were at least able to make a dignified and quiet entrance to our home port.

The coastguards had done their last job for us and we were expected. The Union Jack was hoisted on our garden flagstaff overlooking Castle Cove, the bath water was hot and my mother was sitting in her dinghy on our moorings. So our great adventure was over and we were sorry.

Reproduced by kind permission of Yachting Monthly for on-screen reading only, please do save or reproduce in any other medium.

No comments:

Post a Comment